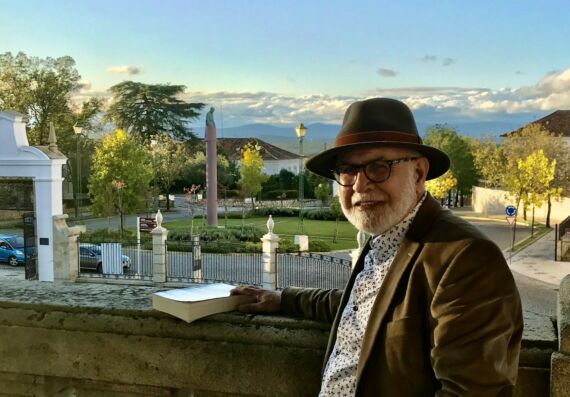

David Cortés Cabán en Castelo Branco, Portugal (foto de José Alfredo Pérez Alencar)

Crear en Salamanca tiene la satisfacción de publicar estos poemas de David Cortés Cabán, traducidos al inglés por Orlando José Hernández y Orly Hernández. Cortés Cabán (Arecibo, Puerto Rico, 1952), posee una Maestría en Literatura Española e Hispanoamericana de The City College (CUNY). Fue maestro en las Escuelas Primarias de Nueva York y profesor adjunto del Departamento de Lenguas Modernas de Hostos Community College of the City University of New York. Ha publicado los siguientes libros de poesía: Poemas y otros silencios (1981), Al final de las palabras (1985), Una hora antes (1991), El libro de los regresos (1999), Ritual de pájaros: antología personal (2004), Islas (2011) y Lugar sin fin (2017). Sus poemas y reseñas literarias han aparecido en revistas de Puerto Rico, Estados Unidos, Latinoamérica y España. En 2006 fue invitado al III Festival Mundial de Poesía de Venezuela, y en 2015 a la Feria Internacional del Libro de Venezuela (FILVEN), dedicada a Puerto Rico. Ha participado en los Festivales Internacionales de Poesía de Cali, Colombia (2013), y de Managua, Nicaragua (2014). En 2014 fue invitado a presentar “Noche de Juglaría, cinco poetas venezolanos”, en Berna y Ginebra, Suiza. Ese mismo año la Universidad de Carabobo, en Valencia, Venezuela, le otorgó la Orden Alejo Zuloaga Egusquiza en el Festival Internacional de Poesía. Reside en la ciudad de Nueva York desde 1973.

David Cortés Cabán estuvo invitado al XXII Encuentro de Poetas Iberoamericanos, a celebrarse en Salamanca del 14 al 17 de octubre DE 2020, bajo la dirección de A. P. Alencart.

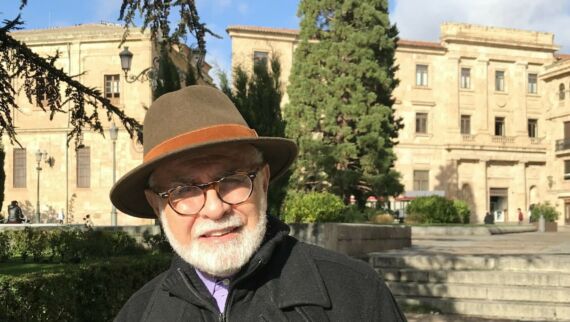

David Cortés Cabán en la salmantina Plaza de Anaya (foto de Luis Borja)

ESTAMOS TRATANDO DE SOÑAR

“Estamos tratando de soñar

pero aún seguimos despiertos”,

le dije a la muchacha en el

Jardín Botánico.

“No es nada extraño”, dijo ella.

“Ahora recojo un girasol, pero

no creo que sea de Van Gogh”.

“Tal vez sí”, dije.

Pero estoy dentro de mi aldea,

una vaca está mirándome, no sé

si es la misma que vi en mi niñez.

“Debes estar soñando con Chagall”, dijo ella.

“Puede ser, siempre quise

vivir en una aldea”, dije.

“Además las vacas de Marc tienen

un lenguaje muy tierno”.

“Es verdad, creo que la vida debe ser

para soñar lo que soñamos”, dijo.

“Estar despierto causa mucho dolor”, dijo

“Me gustaría acompañarte

y pedirle a Van Gogh un girasol

solo para ti”,

“No es posible intervenir en los sueños”, dijo.

“Es cierto”, contesté.

“Además Van Gogh debe estar ocupado

entre sus girasoles”, dijo.

“La fiesta no ha terminado

y nos hemos movido de lugar”, dije.

“Si nos alejamos podrían sorprendernos”, dijo

“Comprendo”, dije.

No conseguimos siempre lo que amamos.

WE ARE STRIVING TO DREAM

“We are striving to dream,

but we are still awake,”

I said to the young woman in the

Botanical Garden.

“There is nothing strange about that,” she said.

“Now I pick a sunflower, but

I don’t think it is one of Van Gogh’s”

“Maybe it is,” I said.

But I’m in my village,

a cow is staring at me, I cannot tell

if it’s the same one I saw as a boy.

“You must be dreaming about Chagall,” she said.

“I could be, I always wanted

to live in a village,” I said.

“Besides Marc’s cows

speak a tender language,”

“That’s true, I think life should be

about dreaming what we dream,” she said.

“To be awake causes too much pain,” she said.

“I would like to go with you

and ask Van Gogh for one of his sunflowers

specially for you,” I said.

“You cannot intervene in dreams,” she said.

“True,” I replied.

“Besides, Van Gogh must be busy

among his sunflowers,” she said.

“The party isn’t over

and we have moved to a different place,” I said.

“If we move too far away, they can discover us,” she said.

“I understand,” I said.

We don’t always get what we love.

David Cortés Cabán recibiendo la distinción del alcalde Carlos García Carbayo (foto de Jacqueline Alencar)

COSAS DEL AMOR

“Yo era un oso hormiguero”,

le dije a la muchacha que me miraba

fijamente en el asiento del tren que nos

conducía a Manhattan.

“Debe ser interesante ser un animal salvaje”, dijo.

“No lo es”, dije. “Hay enemigos por todas partes

y cuando te descuidas caes en las garras

de uno más fuerte”, contesté.

“Después de un tiempo decidí ser lo que soy,

un poeta que viaja entre las nubes”.

La muchacha se sonrió de mi ocurrencia,

y lo inusitado del paisaje que le presentaba.

Justamente a la hora de ir a trabajar

hablábamos de bestias salvajes.

“No es que tenga animadversión por los

animales. Algunos son tan hermosos como un tigre”, dijo.

“Piensas en el tigre de Borges o en el de Blake”, pregunté.

“Solo pienso en cualquier tigre, creo que no tienen dueños”, agregó.

“Es cierto”, dije, “la literatura nos hace creer en fantasías”.

“Debe ser lindo hacer el amor como un tigre”, dije.

“Debe ser una locura, aunque sería fantástico

levantarse una mañana como una tigresa”, dijo.

“Te verías hermosa rugiendo desde una colina”, dije.

“Tú serías el tigre que perdí cuando emigré

a esta ciudad”, dijo. “Es posible”, le dije.

“Los tigres no tienen inhibiciones y se aman en todas partes”.

“La soledad está hecha para los tigres”, añadí.

“Debe ser mágico sentirse una tigresa”, dijo.

“Ya siento que tengo un corazón de tigre”, le dije,

y nos perdimos entre la multitud.

MATTERS OF LOVE

“I was an anteater,”

I told the young woman who was staring at me,

while we were sitting on the train that

was taking us to Manhattan.

“It must be interesting to be a wild animal” she said.

“It’s not,” I said. “There are enemies everywhere

and if you’re careless you’ll fall into the claws

of one who’s stronger than you are,” I went on.

“After some time I decided to be who I am,

a poet that travels from cloud to cloud.”

The young woman laughed at my thought

and the strangeness of the landscape on display.

At the exact same time we were commuting to work,

we were talking about wild animals.

“It’s not that I have animosity toward

animals. Some are as beautiful as tigers,” she said.

“Are you thinking of Borges’s tiger or Blake’s?” I asked.

“I’m just thinking of a tiger, I don’t believe they have owners,” she added.

“True,” I said. “Literature makes us believe in fantasies.”

“It must be nice to make love like a tiger,” I said.

“It must be crazy, but it would be fantastic

if I woke up one morning as a tigress,” she said.

“You would look beautiful roaring from a hill,” I said.

“You would be the tiger I lost when I immigrated

to this city,” she said. “That’s possible,” I told her.

“Tigers don’t have inhibitions and they make love everywhere.

Lonesomeness was made for tigers,” I added.

“It must be magical to feel like a tigress,” she said.

“I already feel I have a tiger’s heart,” I said to her,

and we got lost in the crowd.

Carlos d’Abreu, David Cortés Cabán y Martín Cobano (Foto Beira BaixaTV)

PROBLEMA DE PERSPECTIVA

“¿Entonces este poema es un desorden?”,

le pregunté al poeta mayor.

“Cierto”, explicó:

“la máquina de coser debe ir en la esquina

y el pavo real debe estar en el centro”.

Sentí que existía un problema de perspectivas.

Había pensado que el pavo real

estuviera en la esquina

y la máquina de coser en el centro.

La perspectiva no lo es todo, pensé;

además la máquina de escribir está debajo de la mesa

y debería estar sobre la mesa donde he puesto

la máquina de coser.

Es posible que el poeta mayor

haya confundido la máquina de coser

con la de escribir y el pavo real quedara al fondo,

detrás de la mesa.

“De ningún modo”, advirtió el poeta mayor,

“cada elemento debe ir en su sitio para que el espacio

y la máquina de escribir deban divisarse sin interferencias”.

“Comprendo”, dijo el poeta menor,

“¿pero dónde colocamos al pavo real?”

A MATTER OF PERSPECTIVE

“So this poem is a jumble?”

I asked the major poet.

“True,” he explained:

“the sewing machine must go in the corner

and the peacock in the center.”

Perspective isn’t everything, I thought;

besides, the typewriter is under the table

and it should be on the table, where I’ve put

the sewing machine.

It’s possible that the major poet

has confused the sewing machine

with the typewriter and the peacock

might remain in the background, behind the table.

“Under no circumstances,” warned the major poet;

“each thing must go where it belongs so that the space

and the typewriter can be spotted without interference.”

“I understand,” said the minor poet,

“but where do we put the peacock?”

David Cortés Cabán (Arecibo, 1952) is a Puerto Rican poet who lives in New York City. He taught Spanish in the Modern Languages Department at Eugenio María de Hostos Community College of The City University of New York (CUNY). He is the author of Poemas y otros silencios (1981), Al final de las palabras (1985), Una hora antes (1991), El libro de los regresos (1999), Ritual de pájaros: antología personal (2004), Islas (2011), Lugar sin fin (2017), y Visión poética en tres libros de Alfredo Pérez Alencart (2017).

Translated from the Spanish by Orlando José Hernández y Orly Hernández.

Orlando José Hernández es traductor, crítico e investigador puertorri-queño. Ha publicado libros y ensayos sobre poetas contemporáneos. Sus traducciones incluyen poemas de Lezama Lima, Dionisio Cañas, Elizabeth Bishop, John Ashbery, Gracian y Miranda Archilla, entre otros. En la actualidad prepara la publicación de la breve obra teatral de Eu-genio María de Hostos, ¿Quién preside?, en traducción al inglés.

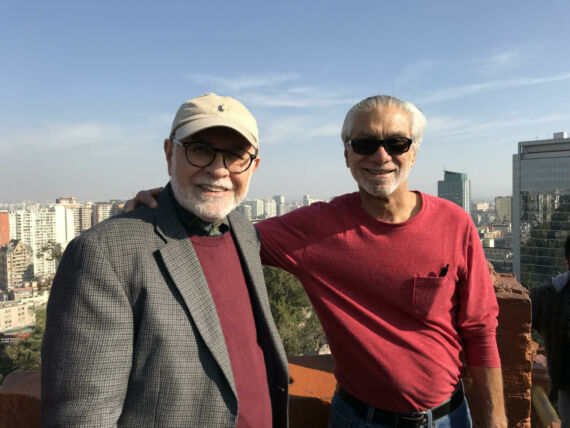

Orlando José Hernández y David Cortés Cabán (Santiago de Chile, mayo, 2019)

Deja un comentario

Lo siento, debes estar conectado para publicar un comentario.